Conducting research can be daunting.

UC Merced, like its sister University of California campuses, prides itself on the opportunities it provides its students to conduct research as part of their educational experiences. But the idea of looking into a concept and producing new results can seem intimidating. Where do you even start?

That's where "Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences" (CUREs) come in. CUREs bring the excitement of research into the classroom to improve learning and the sense of belonging in the field, said UC Merced physics Professor David Strubbe, who recently published a paper on his work in the field.

These experiences can reach more students, earlier in their studies, than typical undergraduate research, said Strubbe, who is also a member of UC Merced's Materials and Biomaterials Science and Engineering (MBSE) Graduate Group. Students learn and use research methods, give input into the project, generate new research data and analyze it to draw conclusions that are not known beforehand.

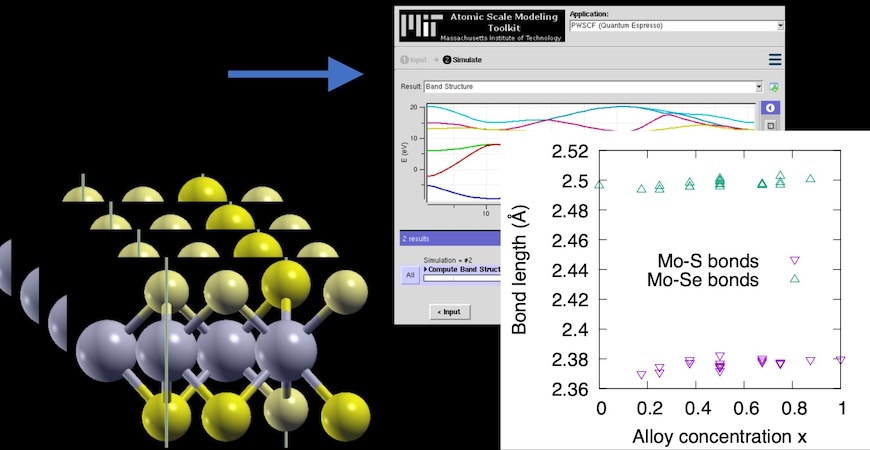

Though CUREs are common in other fields, they have not been used much in materials science and engineering. Strubbe's model for computational materials science CUREs use web-based simulation tools that require minimal computational skills. His work in this area is funded by the CAREER award he earned from the National Science Foundation and by the Cottrell Scholar award.

"The idea is to get undergraduate students into doing research within the framework of a class," Strubbe said. "This could be like a gateway into those more substantial experiences."

Strubbe has used CUREs in two classes, creating a problem where there are many different structures to calculate.

"All the things the students do together add up to a meaningful piece of data," he said. "Overall, it is answering a real research question."

Elsa Vazquez was one of the students who took part in a CURE.

"Everything I knew about research when I started was what I had learned from my peers in my courses or what I heard from the research organizations on campus doing outreach for undergraduates," said Vazquez, a first-generation college student. "I didn't know what it entailed, I just knew that to graduate with my bachelor's, I would want to find a lab and a project that I could join which I could then write my thesis on."

Taking part in research in Strubbe's class taught Vazquez and her classmates both the fundamentals of the research questions they had, and the technical and computational skills required to investigate their questions.

"I think it provides a great environment for students to jump into a research problem with tools that the scientific community is using," said Vazquez, now a graduate student in physics who has worked with undergraduates starting their own research projects. "A CURE offers so much more structure that can't be given in a research project at a conventional lab … this means the students have an appropriate sense of accomplishment and hopefully leave feeling motivated to take on research outside of the course."

That's one of his main goals, Strubbe said: to get students excited about research and give them an idea of what one could do as a professional scientist.

"You don't just solve homework problems," he said. "You figure out new things that nobody knows yet and advance humanity's knowledge."